Twitter @a_dukova

Instagram @policehistorian

Lyndon Megarrity interviews Anastasia Dukova about her recent book To preserve and protect: Policing colonial Brisbane, Australian Policy and History, June, 2020.

The heart of each chapter is the narration of the life and times of a specific historical actor, either a policeman or perpetrator. What do you feel are the advantages of fleshing out historical themes and eras with individual biographies?

Historical criminology demonstrates that policing is not an abstract ideal and cannot be divorced from the social conditions it was borne out of. This approach of interweaving historical themes with individual biographies helps to demonstrate how the organisations and institutions of the time shaped the lived experiences of both policemen and perpetrators. At the same time, it contextualises policing history socially, economically, and culturally. It illustrates cause and effect and how it plays out on an individual level as well as organisationally. It also highlights an existential push and pull between the police and the community. Police would not exist without a community, while a community as we perceive it today would not function without some iteration of law enforcement. The role of the police would be ineffective without community cooperation granting it authority and affording legitimacy.

The drunkards, prostitutes and 'wolf-like larrikins' of 1880s Albert St by Tony Moore, Brisbane Times, 28 June 2020.

Frog's Hollow is named for the noise from hundreds of frogs that once lived in the swampland at Brisbane's Albert and Margaret streets in the mid-to-late 1800s.

But it was also a red light district home to “prowling gangs of wolf-like larrikins,” according to Australian colonial police historian Dr Anastasia Dukova, now working in Brisbane.

'Queensland's First Police Officers were Understaffed, Underpaid ... and Convicts' by Rachel Clun, Brisbane Times, 16 July 2017.

Queensland's police officers may number about 12,000 today, but in the 1820s when the penal colony of Moreton Bay was first established there were only a handful of police constables, and they were all convicts.

In fact, Brisbane's first couple of chief constables were convicts and the main job of early police was locking up drunks. These were just some of the fascinating facts about Queensland's first police officers revealed by Dr Anastasia Dukova, a visiting fellow with Griffith University's Harry Gentle Resource Centre, at the Queensland State Archives.

The new Harry Gentle Resource Centre was started in April to research and publish information on Queensland's history before it became a state in 1859.

'TROVE ON THE BEAT IN BRISBANE: ARRESTING DISPLAY SHOWS COLONIAL CAPITAL WAS A TOUGH TOWN TO POLICE' by Ian Bushnell, National Library Australia, May 2017.

A policeman’s lot was certainly not a happy one in colonial Brisbane, a rough frontier town with an exploding population and alcohol fuelled violence.

Trove did much of the leg work for the Queensland Police Museum’s current display Policing Colonial Brisbane – the Good, the Bad and the Ghastly, and the book by historian Dr Anastasia Dukova, Policing Colonial Brisbane, to be published by University of Queensland Press next year.

Police officers and civilians at Fortitude Valley Police Station; 1880; PM1871 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/197772347?q&versionId=216544257

It also aided the research for Dr Dukova's web project, Digital Colonial Brisbane, funded by Brisbane City Council.

Curator Lisa Jones said the Museum used Trove extensively, especially the digitised newspaper collection, to collect and check information for the display.

Titles included the Brisbane Courier, Telegraph, and the Truth.

Starting with a list of police names, researchers would scour Trove for news clippings detailing their duties, work and life on the mean streets of Brisbane.

Always a risky profession, police would regularly lose skin, their uniforms and their health.

After drunkenness and common assaults, offences against the police were the next most frequent cases tried at the Police Courts.

Digital Colonial Brisbane, drawing on the court report in the Courier, says that “on the night of 16 February 1880, Constable Elliot had occasion to arrest George Hawkins in the centre of Caxton-street, opposite Caxton Hotel, a landmark notorious for overindulging and disorderly behaviour’’.

Hawkins "resisted the constable,’’ reported the Courier, “striking him on the face and other parts of the body. He also bit the constable and tore off a portion of his whiskers. The constable’s face still bore evidence of gross ill-usage. The bench found the defendant guilty, and fined him £3, to be recovered by a levy and distress, or in default of distress, one month’s imprisonment. A cross-case arising out of this, in which Hawkins charged the Constable with assaulting him, was dismissed, after several witnesses had been examined.’’ ('City Police Court', Brisbane Courier, 26 February 1880 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article902464)

Court reports were a rich source of information about the range of cases that came before them – assaults, larceny, drunkards, wife deserters, forgeries.

“We used clips from the police courts. You get all the detail. Newspapers these days are really dull; back then they said everything,’’ Ms Jones said.

The Museum also used Trove to expand the field of inquiry to other sites, publications and collections.

“You can always count on a newspaper report, and that will give you some other clues that’ll allow you to go sideways and point you to another publication, or something else online that you can look up,’’ she said.

For example, early images of Brisbane, and Queensland before separation from NSW, have been obtained from libraries across Australia.

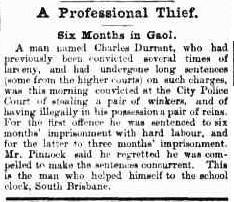

From The Telegraph, Thursday 14 January 1892. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article174037954

Digital Colonial Brisbane includes an interactive Historical Crime Map of the city that “takes visitors along on a beat and lets them experience the bustling, and not always salubrious, street life through the eyes of an ordinary city patrol Constable and an average city dweller’’.

For the book, Ms Jones is writing a chapter on one of Brisbane’s notorious law-breakers of the time, Charles Durrant aka the Tool Stealer and several aliases, who was arrested 64 times between 1888 and 1915.

“There are quite a lot of police references but there were a huge number of newspaper references with all of that court reporting. After a while he was so well known in the court system that they would write about how many times he’d been caught,’’ she said.

Ms Jones is also gathering information on all the police officers in Queensland before separation from NSW, almost exclusively from Trove, by using the search word ‘constable’.

She has already found about 200 names of officers, which will be added to the more than 30,000 entries held in the Museum’s data base.

“I don’t know what we did before Trove. We use Trove every day for everything, whether we’re researching police officers, police stations, criminals , crimes, or early policing,’’ Ms Jones said. “[Before Trove] it took a lot more time and we didn’t have as wider breadth of information to choose from.’’

The Trove Roadshow rolls into Brisbane on Thursday, when you can learn how your collection can join millions of others in the treasure that is Trove.

Find out where the Roadshow is heading here – and book in to join in if we are coming to a town or city near you.

'TROVE ON THE BEAT IN BRISBANE: ARRESTING DISPLAY SHOWS COLONIAL CAPITAL WAS A TOUGH TOWN TO POLICE' by Ian Bushnell, National Library Australia, May 2017 originally published on 15 May 2017 https://www.nla.gov.au/blogs/trove/2017/05/15/trove-on-the-beat-in-brisbane.