Queensland Police

mid 1820s-1830s

Brisbane Town, MB 1830-39

The Brisbane police force that is familiar to us today was over a century in the making. The Moreton Bay penal settlement was established in 1824, the first mention of a local Chief Constable can be traced back to 1828, and like most the inhabitants of the settlement, Chief Constable John McIntosh was a convict. Having said that, unlike the rest of the men, McIntosh was not ‘re-transported’ to Moreton Bay. That is, he did not commit another offence while serving his sentence in the Australian colonies, but rather he volunteered for the transfer.

Between 1826 and 1829 the number of prisoners at Moreton Bay rose from 200 to nearly 1000. The prisoners at the time 'worked the treadmill' for punishment:

The treadmill is generally worked by twenty-five prisoners at a time, but when it is used as a special punishment, sixteen are kept upon it fourteen hours, with only the interval of release afforded by four being off at a time in succession. They feel this extremely irksome at first, but, notwithstanding the warmth of the climate, they become so far accustomed to the labour by long practice as to bear the treadmill with comparatively little disgust, after working upon it for a considerable number of days. (W Coote)

Female Convict Factory ca. 1850 JOL 153725

The town itself consisted of 'the houses of the Commandant and other officers, the barracks for the military, and those for the male prisoners, a treadmill, stores, &c ...Adjacent to the Government House, are the Commandant's garden, and twenty-two acres of Government gardens for the growth of sweet potatoes, cabbages, and other vegetables for the prisoners. Bananas, grapes, guavas, pineapples, citrons, lemons, shaddocks, etc., thrive luxuriantly in the open ground.' (William Coote, History of Colony of Queensland from 1770 to the year 1881, Vol 1. Brisbane, 1882, pp. 24)

In its first five years the Brisbane population increased by more than twenty-fold, from approximately 50 in 1824, the year of settlement, to 1108 in 1829, including 18 female convicts; the very first women to arrive into the settlement, which increased to 71 by 1836. (Pugh’s Almanac 1859, p. 65)

1830s-1850

Richard Bottington (875), QSA

Richard Bottington, also Bettingten, a convict initially transported in 1818 on John Berry (1) from Surrey (plumber, painter, glazier by trade) and re-convicted in Sydney in 1827 for bigamy, took over the Brisbane Police in 1833, only to be succeeded three years later by William Whyte, also a Clerk to the Commandant. In 1840, the police force of Brisbane Town consisted of one Chief Constable William Whyte; Bush Constable George Brown (free); four convicts employed as assistant Constables: Francis Black (arrived on Hadlow), Robert Giles (Exmouth), and W H Sketland ‘or Thompson’ (Sophia), and John Egan.

In 1838, an Act for Regulating the Police in the Towns of Parramatta, Windsor, Maitland and other Towns, etc., was passed in New South Wales. The following year the NSW Border Police was established. In May 1842, NSW Border Police units were organised for the Moreton Bay District. The following year, in January 1843, Captain John Clements Wickham arrived to the town as police magistrate. During the first months of 1843, Chief Constable Fitzpatrick and four men, Ordinary Constables Martin Higgins, Jeremiah Scanlon, James Ramsey and John McGrath were appointed to the local police at a salary of £4 and £2-10-0 respective to their rank, and equipped with muskets and pistols including 80 musket balls and 80 pistol balls for ammunition. (Correspondence from Wickham to CS, Jan-Feb 1843, Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822-1869, SLQ, Reel A2.13, 273, 480-84)

Before joining the local force, William Fitzpatrick previously served with the Sydney Police, leaving with the rank of Assistant Superintendent. (See also entries on Peter Murphy and Samuel Sneyd for more details on CC Fitzpatrick) At the time of his appointment, a Port Macquarie District Constable Peter Duff Murphy was rumoured to have been earmarked for the position. However, given the pushback against the convict police and seeing that he too was an ex-convict, he was passed over.

In 1846, the Brisbane police force comprised of Chief Constable William Fitzpatrick and four constables. Fitzpatrick was dismissed in 1850 and replaced by Samuel Sneyd.

1850s

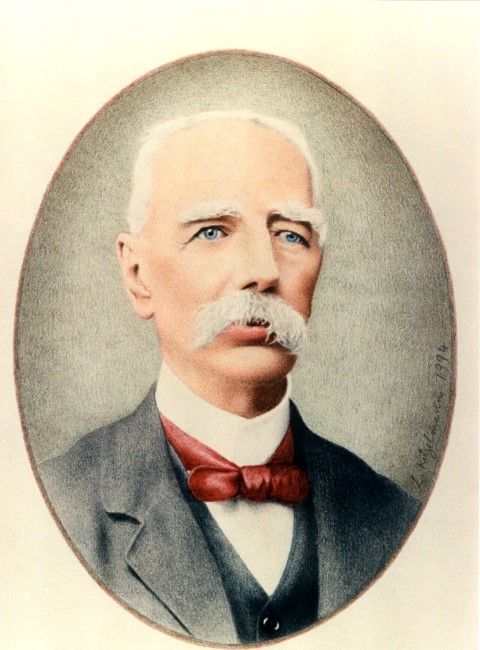

Samuel Sneyd, undated. John Oxley Library Neg 9466.

A new Police Force was organised in 1850. The Act for the Regulation of the Police Force in New South Wales (14 Vic, No.38) provided for establishment of a colonial police force headed by an Inspector General and maintained by a network of provincial inspectors. The proclamation of the act ended locally organised police forces in New South Wales and the domination of the police force by the magistracy, though not for very long. The following year, the Act for the Regulation of the Police Force 1850 was disallowed and replaced by the Police Regulations Act 1852, reinstating rural police firmly under control of their magistrates’ benches. A local Chief Constable continued to receive his orders from the Police Magistrate. New Chief Constable, Samuel Sneyd, was brought over to replace William Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick in turn had replaced Chief Constable William Whyte with his convict policemen in 1843, the same year Captain John Clements Wickham was appointed a permanent Police Magistrate for Brisbane. Four free constables, Martin Higgins, Jeremiah Scanlan, James Ramsey and John McGrath replaced ex-convicts.

In 1859, the year of separation of Queensland from New South Wales, Chief Constable Sneyd retired from the Brisbane Police and took up a post of “a gaoler” at the Brisbane Gaol. Chief Constable Thomas Quirk then took over the force. In mid-1860, it comprised 1 Inspector; 2 Sergeants; 2 Lock-up keepers (North and South Brisbane); 9 Ordinary Constables (North and South Brisbane, Kangaroo Point and Fortitude Valley); 4 Mounted Constables (2 attached to the Government House); 1 Foot Constable (night sentry, Government House); 4 Ordinary Constables as messengers attached to the various colonial administrative offices.

1864-onwards

An Act to Consolidate and Amend the Laws relating to the Police Force, 1863.

Queensland at one time formed a portion of what was included under the general name of New South Wales, and, like the district Sydney proper, was a penal settlement. This ceased to be in 1842; and in 1859 the district of Moreton Bay was erected into an independent colony, under the title of Queensland. (Illustrated Times, London 1863)

Prior to separation in 1859, the area now known as Queensland was governed from Sydney as part of the colony of New South Wales.

In 1850, the Act for the Regulation of the Police Force in NSW (14 Vic, No. 38) provided for establishment of a colonial police headed by an Inspector General supported by a network of provincial inspectors. The proclamation of the act ended locally organised police forces in NSW and the domination of the police by the magistracy. In 1852, however, the 1850 Act was disallowed and replaced by the Police Rgulations Act, reinstating magisterial authority. The same year, William Colburn Mayne (born in Dublin), was appointed Inspector General of Police (1852-56). In 1850 while on Legislative Committee he recommended the local police be reorganised along the lines of the Irish Constabulary. He further suggested the local force be disbanded and replaced by men brought over from Ireland. (Lindsay, True Blue: 150 Years of Service and Sacrifice of the NSW Police Force)

By Letters Patent and an Order-in-Council issued by Queen Victoria on 6 June 1859, Queensland was created as a separate colony. Favouritism of the Irish model persisted. Among numerous the Duties of the Inspector General of the Police in Queenslandoutlined in the Colonial Secretary Papers, 1859-63, one was 'to perform the general duties of the Commandant of the Native Police Force; and to regulate the drill and discipline, dressage of the English Police Force (this should be done as early as circumstances will permit according to the rules of the Police Force in Ireland).' (1860, 69)

Following the separation, the nascent force was mainly concerned with policing Brisbane; the rural areas remained under the jurisdiction of the NSW legislation, even after the QLD Parliament was established in 1860. This taxed the numbers of policemen on duty as the prisoners had to be escorted to Sydney to stand trial. Finally, in 1863, a separate police act was promulgated which took effect on 1 January 1864. 'Candidates with previous service with the Irish Constabulary, urban police or any military/ law enforcement agency were actively sought out for the service. The majority of the Queensland rank and file had Irish links, and officers displayed a strong Irish presence, especially so during the earlier years of the force.' (Dukova, 151)

First Commissioners

In 1864, the population of Queensland was 75,000 with a police contingent of 339 men in a colony stretching over 400,000 miles squared. Of the total strength of the QP, 176 were ordinary constables, and the remaining 163 were members of the Native Mounted Police. (AR 1865) The structure of the organisation was complex and costly to run. In order to accommodate the diverse needs of the colonial topography the following branches made up the force: Water or River Police, Border Police (1839-1865), Native Police and the City or Metropolitan Branch. David Thompson Seymour headed the Queensland Police Force from its inception until 1895. Commissioner of Police Seymour was born and grew up in Ballymore Castle, Galway. Between 1860 and 1909, a total of 1283 Irishmen, approximately 34 per cent of the intake, joined the Queensland Police Force. Seymour's father was a barrister, high-sheriff and lieutenant-colonel of the Galway Militia (Richards, 87) Seymour himself joined the British Army as an ensign at the age of 25, he was promoted to lieutenant in the 12th Regiment following two years of service. 'A detachment from this unit under Seymour's command arrived at Brisbane in 1861. Within a year he became aide-de-camp to George Bowen, the colony's first governor.' (Richards)

William Edward Parry-Okeden (1895-1905), Seymour's successor, was Australian-born of English heritage. His service career began with his enrolment in Melbourne in the Volunteer Force. Parry-Okeden was appointed Commissioner in 1895 and assumed his duties in July of that year. He began his tenure by introducing structural changes to the existing Detective force and establishing the Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB) in lieu. This structural re-ogranisation and the title were modelled on the detective unit of the London Metropolitan Police which was established two decades earlier.

Detectives

Detectives PM0064. Source: Queensland Police Museum and Archives

The Detective Office began on 1 December 1864, 11 months after the inauguration of the Queensland Police Force on January 1. Samuel Joseph Lloyd was placed as the officer in charge of the new branch. Lloyd immigrated to Australia from Ireland and joined the Victoria Police Force in 1855, where he served as a Detective for nearly a decade prior to joining the Queensland Police. Lloyd was OIC of the Detective Branch on and off for the next 32 years, until he retired in February 1896. The number of Detectives in the Office was nominal and drawn basically from the best police officers in Brisbane. There were 2 classes – Detective Constable 1/c and Detective Constable 2/c. Employed only on a part-time basis, the Detectives spent the other part of their time carrying out ordinary police duties. They received no extra pay despite the complicated character of their work and the long hours they often worked in criminal detection. In 1895, Parry-Okened restructured the Office into the specalised Branch, 'half of the men that formed the Queensland CIB were hand-picked, and had previous experience in law enforcement, ranging from the New Zealand Armed Constabulary to the Dublin Metropolitan Police and London Metropolitan Police.' (Dukova, 185)

Beat Policemen

No person shall be appointed Constable unless he shall be of sound constitution able-bodied and under the age of forty years of good character for honesty fidelity and activity and able to read and write.

‘Sir, I respectfully offer myself a Candidate as Constable in the Queensland Police Force’ – all candidates for admission into the Queensland Police Force had to apply in person, with an application in their own handwriting, and such testimonials as they may have. Despite complaints from country hopefuls, who found it difficult to travel to the colonial capital, all men wishing to be considered for the position had to assemble at the Police Depot on Wednesday at 9 o’clock in the morning. The applicants had to be of sound constitution, stand clear at least 5 feet 8 inches without their boots, with chest measurements of 36 inches minimum and 38 inches when expanded. All men had to be free from any bodily complaint. Each applicant was assessed by a medical officer. Initially, the age bar was set to under 40 years old, but was shortly lowered to 30 years old.

Source: Depositions and Minute Books - Police Court. 01/07/1864-15/03/1865 [QSA Item ID 97091].

The conditions of service were arduous and around the clock. The line of duty of the colonial city beat policeman was as extensive and as diverse as that of a Dublin or London bobby: as we have seen, it included an array of responsibilities which ranged from enforcing trading hours to traffic control and from carrying out arrests to recovering missing children. The majority of supernumeraries listed their previous occupation as ‘labourers’, which frequently meant farmers who were not used to rigidly regulated duties. The first years, saw unprecedented turnover of police constables. It was not unknown for a policeman to fall asleep on his beat. Constable Thomas Archibald McArthur (Reg No 1717), Queensland, was fined ten shillings for falling asleep on duty. On the 7 April, 1913, at a quarter after one o’clock at night “while posted for beat duty, found lying asleep on a seat in a park off Leichardt Street.” Constable McArthur resigned later the same year.

Depositions and Minute Books

On September 28, 1864, Constable Michael McKiernan deposed that he has arrested Edward Underwood who was lying drunk on a thoroughfare in Ann Street, Fortitude Valley. The defendant pleaded not guilty. McKiernan swore that the previous evening at half past seven he was on Ann Street where he found the defendant lying drunk on the footway. When asked where he lived, he said ‘any place’ and as no further information was given the Constable took him into custody. On the way to the lockup the defendant resisted violently and struck McKiernan with both hands and feet and tore his tunic, waistcoat and shirt. Underwood was very disorderly and remained so in the lock-up. He was fined 40 shillings including damages.

Long and tedious hours on the beat, wore out not only policemen’s boots and uniforms but their general health as well. Particularly common ailments were rheumatoid arthritis, pleuritis, pneumonia, tuberculosis (‘phthisis’), bronchitis and any contagious diseases rampant at the time (e.g. scarlatina, typhoid fever).

After drunkenness and common assaults, misdemeanours against Constables on duty formed the most prominent sub-category tried at the City Police Court. Throughout the nineteenth century, one of the most prevalent offences was destroying a policeman’s uniform. Nearly every other arrest would result in some damage. The degree of damage often varied and ranged from merely a button being bitten off to torn ‘tunic, waistcoat and shirt’.

various duties of a brisbane policeman

A Brisbane city policeman was truly a jack-of-all-trades. Apart from the extensive policingduties (peace preservation, crime prevention, prosecution, beats), duties, he was expected to fill in the gaps in the civil service system. The services hitherto performed by him were not at all police duties, but occupied a considerable portion of a policeman’s time. Even well into the twentieth century, the extraneous duties list contained on average fifty to eighty tasks. In his first report to the Parliament, Seymour alluded to these services, namely ‘summons-serving, acting as Clerks of Petty Sessions, rangers of Crown lands, inspectors of Slaughter-houses, district registrars of births, deaths, and marriages, and bailiffs of Courts of Requests - none of which duties are legitimately those of constables.’ For example, according to the Police Court report printed by the Brisbane Courier, James Lovett appeared to answer a summons for breaching a Town’s Police Act, when he was ordered to pay a total of 10 shillings (a fine and costs of court) for depositing manure on the North Quay (city centre). How much police time this took up can only be imagined.

REFERENCES

![Source: Depositions and Minute Books - Police Court. 01/07/1864-15/03/1865 [QSA Item ID 97091].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56637e60e4b032b04c6199e1/1524739285256-O5H5FLAGKDKH58GXSI1T/28.09.64+2+%281%29.JPG)